Tucked away in a staircase in the huge building of Vienna’s Natural History Museum, between the second and third floors, there is a small exhibit about the history of the museum that devotes a lot of space to the early history of the collection (and virtually none to those seven years after 1938 the Viennese would rather forget about). In one of these cases one can find the little statue pictured above, a concoction created by a Dr. Friedrich König. Apparently an forgotten figure in the history of Paleoart, König’s statues show him to be a link between American, British and Central European approaches to depicting extinct animals.

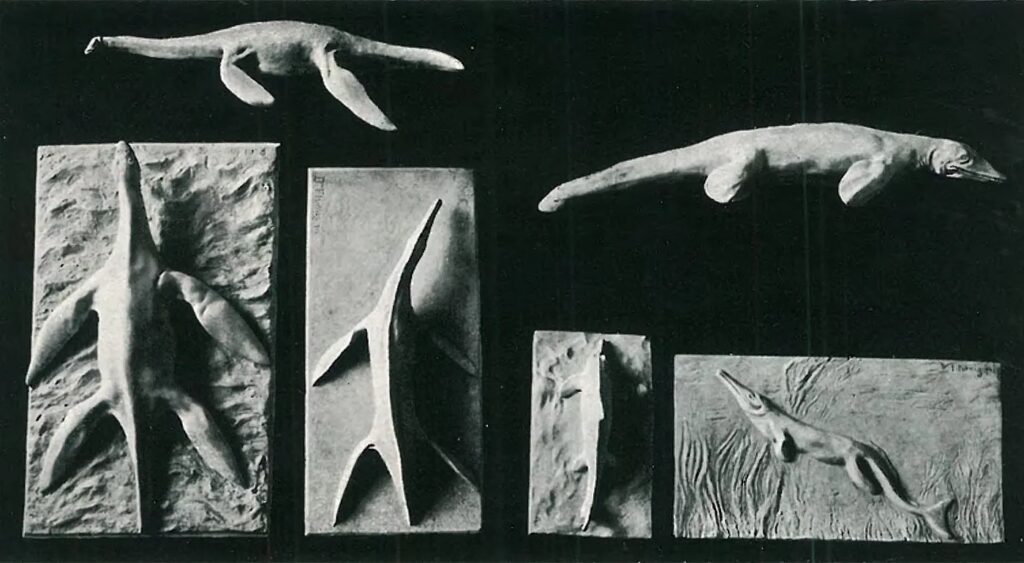

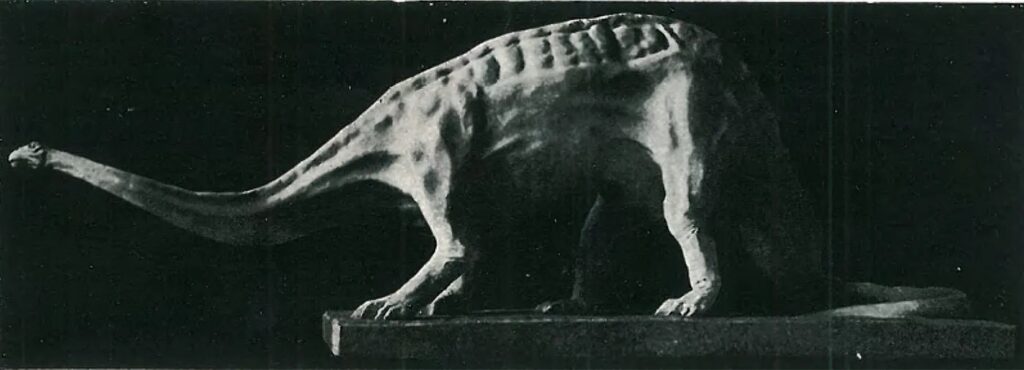

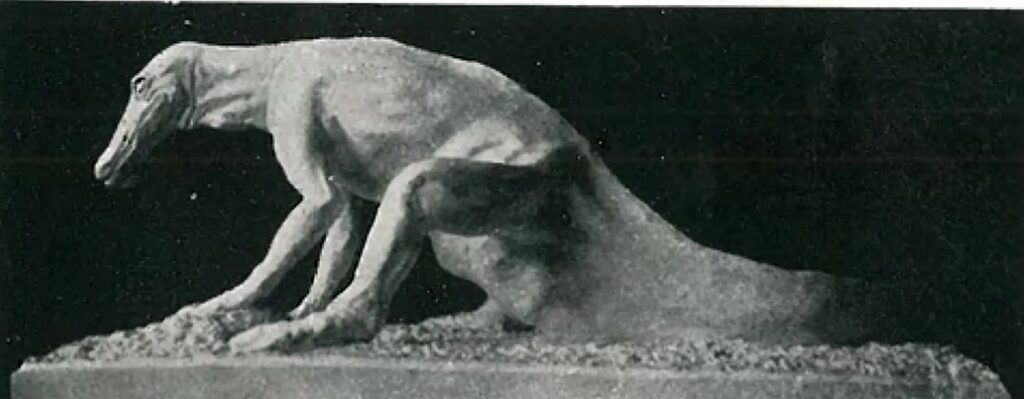

Now, I already knew König from a little catalogue he produced in 1911, which contained a series of plaster reconstructions of extinct animals* König’s book, which seems clearly aimed at natural history museums, is particularly interesting because it includes endorsements by Othenio Abel (an Austrian pioneer of paleobiology, who refers to König as his “former student”), Eberhard Fraas (the first paleontologist to see the Tendaguru remains), and the Munich paleontologist Max Schlosser. These ranked among the most prominent specialists in the germanosphere.

For me the most fascinating part follows these endorsements. König takes several pages to explain his choices in reconstructing the animals. This essay shows good familiarity with the scientific literature of the age, and tells how these have been translated into the reconstructions.

And those reconstructions are in fact exquisite, and for the most part unlike anything else. Especially his Stegosaurus is very individual. Seeing them “in the flesh” also explains why he came recommended by such luminaries as Othenio Abel, Eberhard Fraas, and the aforementioned Broili. The exception is König’s model of Triceratops prorsus, which appears to be an almost literal copy of Charles Knight’s famous 1901 model. At the time, Knight’s work was anything but common knowledge in Central Europe, and other manufacturers of similar models generally used a different template – either indigenous or inherited from older British and French examples.

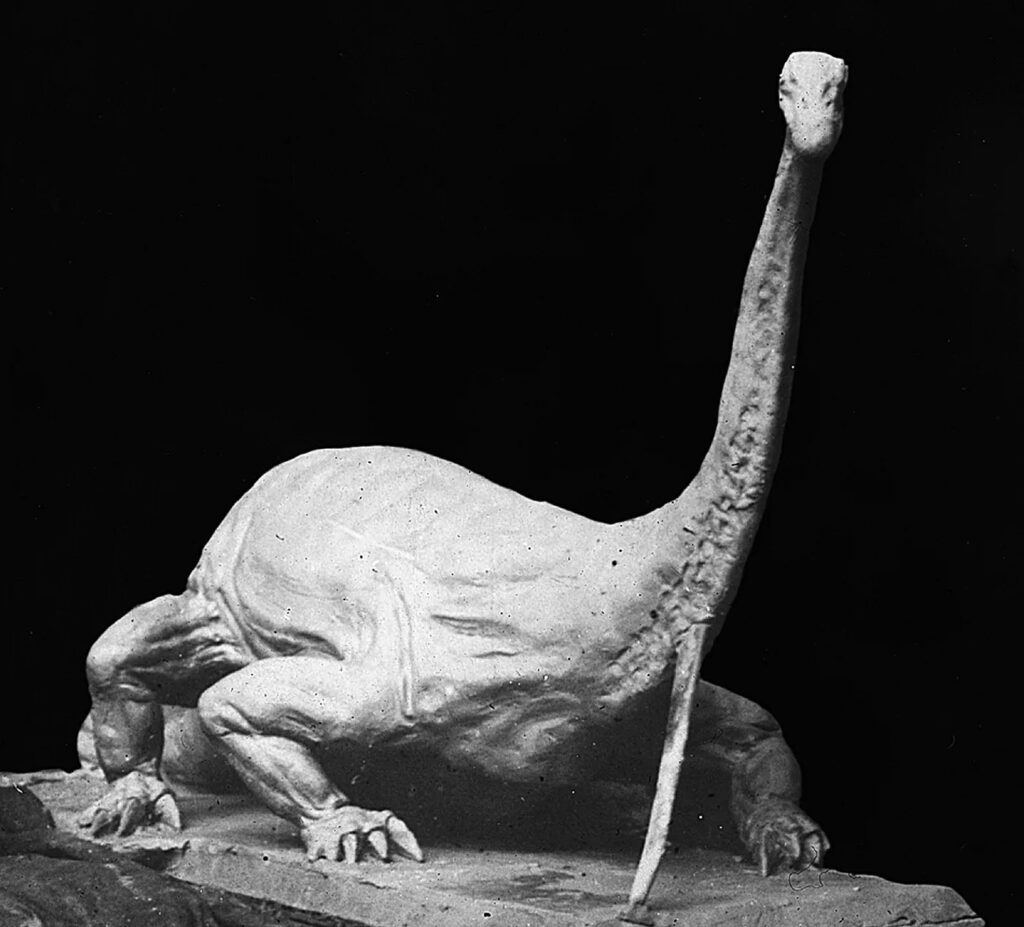

Both crouching and standing

König makes an effort to remain out of controversies. While the sauropod dinosaur Diplodocus is reconstructed as standing upright (“after Abel”) in the catalog, König also offers a reconstruction of a “Tornierian”, crawling Diplodocus (“nach Tornier reptilhaft kriechend”).? However, only the former is included in the booklet; a picture of the latter was distributed as a separate insert. Considering Abel’s endorsement this is not surprising, and one wonders whether it might have been a condition for it. After all, this was published in the middle of the “crawling Diplodocus” controversy. The resulting Diplodocus surprisingly looks even more Abelian than Abel’s own reconstruction.

With such first-rate support, one might have expected König’s venture to do well, but sofar I had not seen any of his models “in the flesh”, so to speak. All made of plaster, they are excellent examples of the mainstream German paleontological thought of the day. But from the catalog they come across as a bit cruder than what we’re used to from the likes of Knight or Pallenberg; surpisingly, in “real life” they look far more artistic.

After what appears to have been only a brief stint in paleoart, König seems to have concentrated on advertising work (for which he attached his mother’s surname, Lorinser, in front of his own).

König’s models in the wild

Apart from Vienna, the Staatssammlung für Paläontologie und Geologie contains a fairly good selection of Königs statues, which they exhibited in 2020. König worked out of Munich himself, so one would expect the local museum to have a good representation of his work – the more so since his catalogue prints an explicit recommendation from Ferdinand Broili, then director of the institute

The models hardly show their age of more than a century, and look far more life-like and dynamic than the catalogue represents. The difference is actually quite startling, and suggests that König’s apparent lack of commercial success might have been caused at least partially by questionable photography and print work. This is admittedly anecdotal speculation; I just haven’t encountered his models much. The University of Greifswald possesses a model of the Plesiosaur Dolichorhynchops osborni, purchased around 1910 by Otto Jaekel, a close acquaintance of Abel.

It is difficult to ascertain whether other museums purchased König’s works, but their old-fashioned nature might would probably long ago have removed them from their display cases. On the other hand, Knight’s statues are still everywhere, as are many by Pallenberg (especially his Iguanodon). So this might be a indicative of König’s lack of commercial success perhaps. Also, World War I probably didn’t help in persuading museums (especially those outside of Germany and Austria) to buy these excellent statues.

N.b. Abel’s role in science and politics is discussed extensively in a number of publications. For a good overview of his scientific work, see Rieppel, Olivier (2013). “Othenio Abel (1875-1946): The Rise and Decline of Paleobiology in German Paleontology.” Historical Biology 25, no. 3: 313-25. The political dimension of his life (short summary: fiercely anti-semitic, pro-nazi and generally nasty) has more recently been explored by Klaus Taschwer: Taschwer, Klaus (2015). Hochburg des Antisemitismus. Der Niedergang der Universität Wien im 20. Jahrhundert. Wien: Czernin.

Literature

- Abel, Othenio (1910). “Die Rekonstruktion des Diplodocus.” Abhandlungen der K. K. Zoologisch-botanischen Gesellschaft in Wien 5: 1-59.

- König, Friedrich. Fossil-Reconstruktionen. Bemerkungen zu einer Reihe plastischer Habitusbilder fossiler Wirbeltiere. München: E. Dultz & Co., 1911. 5.